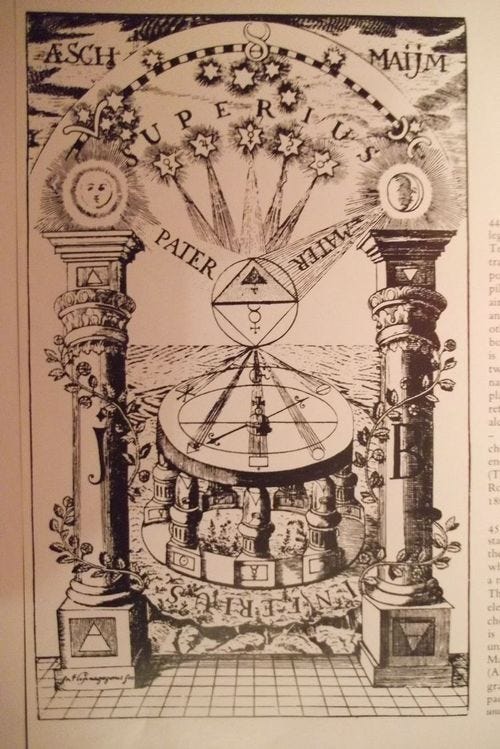

It shall be found, In the filth

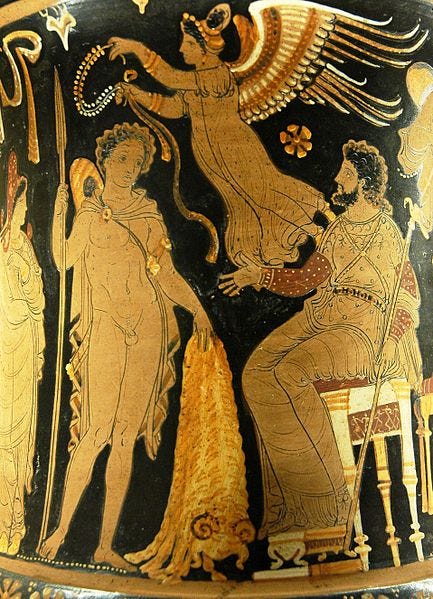

The fleece of the golden-woolled winged ram named Chrysomallos was legended to bestow royal power to its owner. In the kingdom of Iolcos lived Jason, son of King Aeson. Pelias, son of Poseidon and half brother of Aeson, dethroned the King locking him in the dungeons of Iolcus. Pelias, fearing Jason would kill and dethrone him, sent him on an impossible task to retrieve the legendary Golden Fleece.

The Golden Fleece was an impossible relic only bestowed through an impossible task.

Jason and the Golden Fleece is an ancient story about a hero and his journey.

In Joseph Campbell’s1 1949 book The Hero with a Thousand Faces, he describes a theory of the journey of an archetypal hero called the monomyth. The hero's journey is a generalized story structure describing a character who departs on an adventure, overcomes a decisive crisis, and returns home changed and transformed.2

Discovered through a comparative analysis of world mythologies, Campbell describes the seventeen stages and three acts of the hero’s journey. Since the debut of his theory, there have been numerous variations, summaries and applications of the monomyth.

“You enter the forest at the darkest point, where there is no path. Where there is a way or path, it is someone else's path. You are not on your own path. If you follow someone else's way, you are not going to realize your potential.”

― Joseph Campbell, The Hero's Journey

World mythologies follow no strict symbol conventions, which allows storytellers to convey a wide variety of interpretations depending on the reader’s state of mind. With an ability to encode numerous concepts, the monomyth has been used to express mystical / metaphysical ideas, cosmological concepts, social conformity and nonconformity themes, and psychological guides through the passage of life.

The study and analysis of the hero’s journey is not limited to literary analysis, but also communicates esoteric ideas like the "Right Hand Path," "Left Hand Path," and inner psychological archetypes.

While the hero’s journey may convey any number of messages, it can also help us understand our own internal conflicts. This was the inspiration Campbell drew from Carl Jung3 and his work on the ego, the unconscious and analytical psychology.

Jung described the human psyche as a composition of archetypal figures, including the anima / animus, the shadow, the collective unconscious, the self, the persona, and many more. The hero’s journey in the context of analytical psychology is an inward call to adventure that explores the psyche through a descent into the unconscious mind, aiming to resolve conflict through archetypal inner dialogue.

Jung described the forgotten and unknown recesses of the unconscious as the filth. The prima materia (i.e., presenting problem) is resolved only by travelling into the filth to find the precious thing that resolves the problem.

The prima materia is “saturnine,” and the malefic Saturn is the abode of the devil, or again it is the most despised and rejected thing, “thrown out into the street,” “cast on the dunghill,” “found in filth.”

— Carl Jung, Mysterium Coniunctionis

The filth is a concept from alchemy, claiming that the thing we want the most is found where we want to look the least. For a Jungian analysis, the place we want to look the least is deep within ourselves, in the filth we bury subconsciously. That is the hero’s journey into hell from the context of analytical psychology.

Sterquiliniis Invenitur.

(In filth, it will be found.)

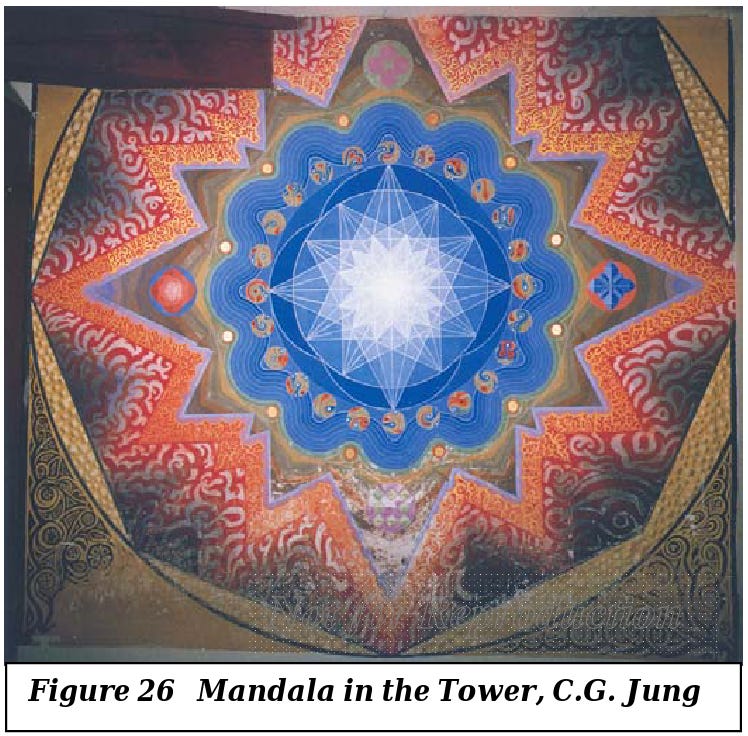

At the age of 38, Carl Jung faced a horrible confrontation with his unconscious psyche, experiencing visions and hearing voices. He catalogued his menacing psychosis in a Black Book, and decided to confront this inner terror through the use of active imagination in private sessions.4 His techniques induced hallucinations that led him through imagined dialogue with inner figures and symbols. Eventually, he authored a leather-bound red book containing his transcribed notes and paintings.

My soul, my soul, where are you? Do you hear me? I speak, I call you–are you there? I have returned, I am here again. I have shaken the dust of all the lands from my feet, and I have come to you, I am with you. After long years of long wandering, I have come to you again....

Do you still know me? How long the separation lasted! Everything has become so different. And how did I find you? How strange my journey was! What words should I use to tell you on what twisted paths a good star has guided me to you? Give me your hand, my almost forgotten soul. How warm the joy at seeing you again, you long disavowed soul. Life has led me back to you. ... My soul, my journey should continue with you. I will wander with you and ascend to my solitude.

— Carl Jung, Black Book first entry (Nov. 12, 1913)5

Biographer Barbara Hannah compared these imaginative experiences to Menelaus with Proteus in the Odyssey.6 The hero’s journey describes Jung’s inner descent, where he confronted his schisms and personal / collective demons. Through this experience, he allegedly developed his renowned psycho-analytical principles and theories relating to archetypes, and the process of individuation.

But not every journey is heroic.

Filling the conscious mind with ideal conceptions is a characteristic feature of Western theosophy, but not the confrontation with the shadow and the world of darkness.

One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light, but by making the darkness conscious. The latter procedure, however, is disagreeable and therefore not popular.

— Carl Jung, Collected Works 13: Alchemical Studies, Paragraph 3357

The hero’s journey is summarized as:

Ego death.

Confronting the darkness.

Divine rebirth.

Now, imagine its opposite.

Divine death.

Occulting the darkness.

Ego rebirth.

That is the anti-hero’s journey.

Mystically, these are respectively the “Right Hand Path” and “Left Hand Path.”

Many on the anti-hero’s journey mistake theirs as the path of righteousness.

The brilliance of an ideal reality, and its temptations to be the master of good and evil, is the false light leading to darkness. The anti-hero’s journey hides the shadows created by the ideal, and places the ego above all else. If the hero’s journey is to discover the truth, then the anti-hero’s journey is to hide it through dark fictions.

Many believe they are the good guys in their personal story, and characterize “the other” as a cartoonish bad guy. After all, for the play to go on, all truth must be hidden through darkness, acts and masquerades.

There are spiritual cultures, parallel to the anti-hero’s mindset, that sympathize with heavenly rebels bringing grandiose promises of gnosis and liberation.

H. P. Blavatsky’s influential The Secret Doctrine (1888), one of the foundation texts of Theosophy, contains chapters propagating an unembarrassed Satanism. Theosophical sympathy for the Devil also extended to the name of their journal Lucifer, and discussions conducted in it. To Blavatsky, Satan is a cultural hero akin to Prometheus.

According to her reinterpretation of the Christian myth of the Fall in Genesis 3, Satan in the shape of the serpent brings gnosis and liberates mankind. The present article situates these ideas in a wider nineteenth-century context, where some poets and socialist thinkers held similar ideas and a counter-hegemonic reading of the Fall had far-reaching feminist implications.

— Blavatsky the Satanist: Luciferianism in Theosophy, and its Feminist Implications8

Beware the brightest star in mourning.

Its false light leads to darkness, and a lake of ice at the bottom of the well.

Like lightning from heaven, the aristocrats of the old world have fallen to darkness.

Degenerating through self-righteousness fits and psychotic grandiose delusions, these old world aristocratic elite lead the masses through the twin fasces9 of the broad gate, glorifying their ego above all; symbolized by the “I” at the top of a pyramid. These are the egos that sit at the top of corporate, government and international power.

Beware those who masquerade as servants of righteousness.

Accepting the call of the hero’s journey is no easy task.

In its first act, the ego and its many fictions are sacrificed; achieved by confronting the darkness, and searching in the filth for truth. A treacherous path. Expect to walk through hell and face many trials. But you will find what you yearn for the most; your soul, which has been imprisoned in the filth and its labyrinth of fiction. You will return home disillusioned with your spirit made whole.

Each story has multiple meaning; it’s one of their true powers. Everyone has a different journey and a different hell. We must travel to where we wish to travel the least. To the filth within and to the filth without. The journey through the inner worlds must be matched by a journey in our outer world.

There must be practical real world work!

Out of our direct control is the filth above; thus, observe the filth below.

The filth below is a provider for our mysterious organic life; a wriggling, putrid and squishy life sustaining realm. Our physical cells are the symbiosis of microorganisms; the proverbial atoms from the realm below. Those fearing the carbon in the air should seek the wares from the merchants below. Hoard carbon in the earth, feed the lower realm, and nourish the tree of life.

Listen for the call to adventure!

And descend into the realm below.

(I’m talking about composting and regenerative gardening.)

Doesn’t sound so cool now does it?

Our heroic journey begins by venturing through the darkness within in the search of our soul, and sacrificing our body and mind to the dark soil below. Beware the false path on the left, the one glittered with righteousness and tempting fictions, which leads to the top of a pyramid that plunges straight into the deepest parts of hell.

The journey is full of filth, like compost, fungi, soil science, boring textbooks…

And personal trauma… and personal trauma created by the boring textbooks…

Are you ready for your heroic journey?

Joseph Campbell (Mar. 26, 1904 – Oct. 30, 1987) was an American writer.

Campbell, J. (2010). The hero with a thousand faces. Fontana Press.

Carl Jung (Jul. 26, 1875 – Jun. 6, 1961) was a Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst.

Jung, C. G. (Oct. 2020). "Editors Note". In Shamdasani, Sonu (ed.). The Black Books of C.G. Jung (1913–1932). Stiftung der Werke von C. G. Jung & W. W. Norton & Company. Volume 1 p. 113.

Jung, C. G. The Red Book: Liber Novus, ed. Sonu Shamdasani, tr. John Peck, Mark Kyburz, and Sonu Shamdasani (WW Norton & Co, 2009), p. 232

Hannah, Barbara (1976). Jung: His Life and Work. p. 115.

Jung, C. G. (2023). Collected works of C.g. jung: Alchemical studies (volume 13) (G. Adler, M. Fordham, & Herbert Read, Eds.; R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). Taylor & Francis.

Faxneld, P. (2013). Blavatsky the Satanist: Luciferianism in Theosophy, and its Feminist Implications. Temenos, 48(2). https://doi.org/10.33356/temenos.7512

i.e., The twin fasces is fascism.

I love me some permaculture, and a big thing there is turning your waste into your fertilizer. There’s some gnarly symmetry with that idea about how to grow food, and this Jungian filth you’re talking about that is right there waiting for you to grow yourself from it

Top shelf